I have had the habit for some years now that, when I come across an interesting article about P.G. Wodehouse, I copy it into my electronic Wodehouse folder, ready for use in some future, as yet unknown, piece, as Bertie Wooster would call it. Then, of course, I forget all about it.

Days, weeks, months, even years later I’ll be trawling through the folder, which has no rules or structure or anything other than alphabetical order, when I come across an opaque filename. “Ho,” say I to myself, in the manner of Constable G. D’Arcy Cheesewright, “what’s all this then?” You know what it is, don’t you? Yes, it’s the anecdote or observation I needed to fill out properly the story I’ve just published, or the talk I’ve just given. Dammit.

Frustration has burst upon me again in this way but for once I have frustration fooled – unlike in past instances it is not yet too late to add to the yarn. What follows therefore is a lengthy addition to Pelicans and Pink ’Uns – Wodehouse in Clubland, posted before Christmas, plus a bit more. My curiosity led me down an unexpected path.

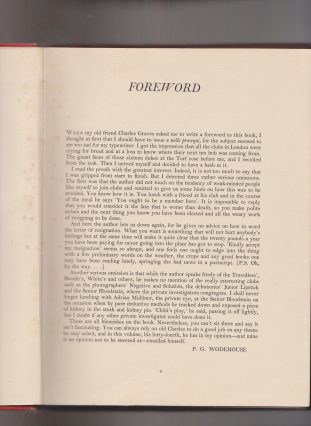

Confined to barracks the other day because it was 43deg. outside, I was browsing my folders in search of something to do when I came across a file labelled “intro to Leather Armchairs by Charles Graves” and dated 23 February 2017. When opened, this comprised a single page in JPG format, headed FOREWORD and signed P.G. Wodehouse. It carried no note about where it came from. It was not a photo in my phone, and I had no record of receiving it by e-mail or any other means. The look of it, though, indicated it was scanned from a book flattened out on a printer plate, and that meant it could only have been done by me. After a moment’s reflection I reckoned I knew the source. I Googled “Leather Armchairs by Charles Graves” . . .

Confined to barracks the other day because it was 43deg. outside, I was browsing my folders in search of something to do when I came across a file labelled “intro to Leather Armchairs by Charles Graves” and dated 23 February 2017. When opened, this comprised a single page in JPG format, headed FOREWORD and signed P.G. Wodehouse. It carried no note about where it came from. It was not a photo in my phone, and I had no record of receiving it by e-mail or any other means. The look of it, though, indicated it was scanned from a book flattened out on a printer plate, and that meant it could only have been done by me. After a moment’s reflection I reckoned I knew the source. I Googled “Leather Armchairs by Charles Graves” . . .

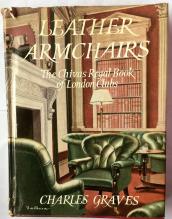

Bingo. This immediately produced a book reference, Leather Armchairs: The Chivas Regal Book of London Clubs, which confirmed my suspicion the page most probably came into my possession from the Melbourne Savage Club library. I don’t have the book – at least I hope I don’t, because I wouldn’t like to think I didn’t return it and it is now lost among the hopeless mess that is my library. I must have come across it at some stage when I was looking for something else on the club bookshelves, maybe even to do with London clubs although there’s nothing in my scribblings from the time to suggest what.

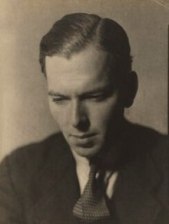

The book is, as the title indicates, a catalogue of London’s gentlemen’s clubs sponsored appropriately enough by the makers of Chivas Regal Scotch whisky and published in 1963. The author, Charles Graves (1899-1971), is more interesting. A veteran journalist and author, he was the brother of Robert Graves (poet, author of, inter alia, the famously dramatised I, Claudius and its sequel) and, despite a nearly 20-year age difference, an old pal of Plum from the high-living days of the twenties and thirties. More than that, when I looked up Graves in the Wodehouse biographies, I discovered a story much better than a bit of trivia about Plum doing a favour for a mate.

The book is, as the title indicates, a catalogue of London’s gentlemen’s clubs sponsored appropriately enough by the makers of Chivas Regal Scotch whisky and published in 1963. The author, Charles Graves (1899-1971), is more interesting. A veteran journalist and author, he was the brother of Robert Graves (poet, author of, inter alia, the famously dramatised I, Claudius and its sequel) and, despite a nearly 20-year age difference, an old pal of Plum from the high-living days of the twenties and thirties. More than that, when I looked up Graves in the Wodehouse biographies, I discovered a story much better than a bit of trivia about Plum doing a favour for a mate.

So what did P.G. Wodehouse say about his chum’s clubland encyclopedia?

So what did P.G. Wodehouse say about his chum’s clubland encyclopedia?

He began: “When my old friend Charles Graves asked me to write a foreword to this book, I thought at first I should have to issue a nolle prosequi . . .” This is classic Wodehouse – his characters issued many such notices of disengagement over the years, and Plum always adopted a self-deprecating style when writing about himself. The tone here echoes another book intro he wrote for Graves (pictured) as far back as 1930 and quoted by Frances Donaldson in her, in turn, self-deprecating preface to her biography of P.G. Wodehouse (1982).

Anyway Plum thought he would have to turn down Graves’ request because he was under the impression (from the United States) that London clubs were not travelling too well financially and the whole enterprise would be too sad. In his day Wodehouse was a member of six London clubs, most of them simultaneously, and invented quite a few more. But he read the thing and “nerved” himself to have “a bash at” a foreword as requested.

“I was gripped from start to finish,” Wodehouse wrote. “But I detected three rather serious omissions. The first was that the author did not touch on the tendency of weak-minded people like myself to join clubs and omitted to give us some hints on how this was to be avoided. You know how it is. You lunch with a friend at his club and in the course of the meal he says ‘You ought to be a member here’. It is impossible to reply that you would consider it the fate that is worse than death, so you make polite noises and the next thing you know you have been elected and all the weary work of resigning to be done.”

This led Wodehouse to what he believed was Graves’ second omission – advice on how to word a resignation letter: “What you want is something that will not hurt anybody’s feelings . . . ‘Kindly accept my resignation’ seems so abrupt, and one feels one ought to edge into the thing with a few preliminary words on the weather, the crops and any good books one may have been reading lately, springing the bad news in a postscript. (P.S. Oh, by the way . . .).”

The third complaint was that Graves failed to mention some really interesting clubs, such as the photographers’ Negative and Solution and the debutantes’ Junior Lipstick. “I shall never forget,” wrote Plum, “lunching with Adrian Mulliner, the private eye, at the Senior Bloodstain on the occasion when by pure deductive methods he tracked down and exposed a piece of kidney in the steak and kidney pie.” In case you haven’t figured it out, Plum delved into his own files to give Graves a couple of free jokes.

Wodehouse reckoned the book was fascinating despite the “omissions” and concluded: “You can always rely on old Charles to do a good job on any theme he may select, and in this volume, his forty-fourth, he has in my opinion – and mine is an opinion not to be sneezed at – excelled himself.”

Which was very generous of Wodehouse, given that he more than likely knew of the role Graves played (albeit somewhat inadvertently) in the vilification of Wodehouse in Britain and the US after his infamous 1941 broadcasts from Berlin. Frances Donaldson quotes in her Wodehouse biography the relevant passages from Graves’ autobiographical “diary”, Off the Record, detailing how the almost equally notorious Cassandra BBC broadcast about Wodehouse came to be created and put to air. Graves attended a lunch with Duff Cooper, the Minister of Information, and others at which what to do about Wodehouse’s broadcasts was discussed. Graves suggested that something be said after the nightly BBC news. Various lightish formats were dismissed by Duff Cooper who thought they were too soft. But one of the attendees, William Connor, who wrote a column in the Daily Mirror under the name of Cassandra, suggested he broadcast to America on the subject of Wodehouse’s (alleged) tax evasion. Duff Cooper jumped at the idea. The BBC rejected it because the circumstances of Wodehouse’s actions were not known. But Duff Cooper enthusiastically embraced the script Connor produced and directed the broadcaster to air it, which the BBC duly did under strong, written protest.

Connor, who had earlier unburdened himself against Wodehouse in his Cassandra column, began his talk: “I have come to tell you tonight of the story of a rich man trying to make his last and greatest sale – that of his own country . . . It is the record of P.G. Wodehouse ending forty years of money-making fun with the worst joke he ever made in his life.” This set the tone for the years of accusations and abuse that followed.

Connor, who had earlier unburdened himself against Wodehouse in his Cassandra column, began his talk: “I have come to tell you tonight of the story of a rich man trying to make his last and greatest sale – that of his own country . . . It is the record of P.G. Wodehouse ending forty years of money-making fun with the worst joke he ever made in his life.” This set the tone for the years of accusations and abuse that followed.

William Connor (1909-1967) built his whole career on his biting wit and sarcasm, for which, like Plum, he was duly knighted by a grateful Sovereign. He is famous for beginning his first column after war service: “As I was saying before I was so rudely interrupted . . .” Curiously, the book of collected columns that I took down from my shelves for this post contains nothing from before 1948.

Graves recorded his opinion of the Plum problem in Off the Record (1942): “He [Wodehouse] was cut off from the rest of the world at England’s darkest hour – Dunkirk. Since then he has heard nothing except what Goebbels has pumped into him, & it would not surprise me in the least if he genuinely thought he was doing us and the USA a good turn with his talks . . . He is the last man in the world to be doing what he is doing if he really knew the truth.” Nevertheless, as Donaldson pointed out, he was responsible for the conversation which led to Connor’s broadcast.

Official inquiries cleared Plum of everything but a disastrous lapse of judgement – a verdict kept secret until 1980, five years after his death. Neither he nor Connor knew that verdict when they met over lunch in New York in 1953 and Plum charmed Connor into a friendship which resulted in Connor recanting. While Wodehouse is entirely to blame for what he did, and never excused himself, it was the continued vilification after the war, in the absence of any real knowledge, that played a major role in his exile to America. When finally forgiven with a knighthood (at the instigation, it is believed, of the Queen Mother) he was much too frail to travel “home” to receive it. Indeed he died six weeks later on 14 February 1975, aged 93.

The peculiar thing about the Wodehouse talks I have given at the Savage Club is the continued lively interest in Plum’s wartime misadventures. To my dismay, this sometimes overtakes the intended light-hearted discussion and celebration of his works and literary legacy. I try to keep these lunchtime chats anchored to the jokes, the similes, the metaphors and generally the wide world of Wodehouse. That is all the clubland chat was about but I spent some considerable time after it under intense questioning about Wodehouse, the traitor and/or the Nazi sympathiser.

I accept that much of this kind of interrogation is an attempt to bait me, for I am among good friends and they know how to stir me up. That’s what mates do for fun over a convivial or two. But sometimes it gets in among me to no little extent and I want to dive into the detail to show the accusers how wrong they are. I resist the impulse, though, and I’ll continue to resist it because nothing could be duller than a lunch mired in hunting, like Adrian Mulliner seeking his piece of kidney, for the truth about Wodehouse’s war.

Only one man knew that for certain, and he’s dead. Fortunately, he left us a great legacy.

FOOTNOTE: Always a damned footnote, isn’t there? This one should interest my Savage Club readers (both of them). The Robert Menzies Collection, papers of Australia’s Prime Minister and long-serving president of the Melbourne Savage Club held at Melbourne University, lists a copy of Leather Armchairs among its possessions and notes: “Reference to Robert Menzies on page 81 referring to occasion when Menzies wore the Savage Club tie to a meeting with Colonel Nasser.” Don’t ask me to explain who Nasser was. All I’ll say is that he never captained England at cricket.

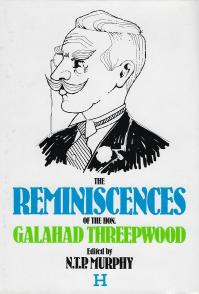

Through several books, before the Empress [the pig, remember . . . please keep up] eats his manuscript, he keeps busy writing his memoirs of scandalous gallivanting around the haunts of old London. Murphy claims Gally rewrote these tales, bequeathed them to him and he (Murphy) has published them as the Reminiscences of Galahad Threepwood. The book mostly combines stories of the real Pelicans and Pink ’Uns with some fictional ones featuring Gally’s pals like Plug Basham, Tubby Parsloe and Barmy Twistleton (otherwise known as Uncle Fred). Murphy said there were only 16 pages of fiction in the book and defied anyone to identify them.

Through several books, before the Empress [the pig, remember . . . please keep up] eats his manuscript, he keeps busy writing his memoirs of scandalous gallivanting around the haunts of old London. Murphy claims Gally rewrote these tales, bequeathed them to him and he (Murphy) has published them as the Reminiscences of Galahad Threepwood. The book mostly combines stories of the real Pelicans and Pink ’Uns with some fictional ones featuring Gally’s pals like Plug Basham, Tubby Parsloe and Barmy Twistleton (otherwise known as Uncle Fred). Murphy said there were only 16 pages of fiction in the book and defied anyone to identify them.