Anyone who has an affinity with the English language and happens to be in London would be well rewarded by braving the crowds and paying the moneylenders at Westminster Abbey just to visit Poets’ Corner.

You’ll be able to sit there for a while, among the slabs of stone and the pompous statues commemorating many of the greatest exponents of our tongue, and ponder why it is that in a place given over to tombs and memorials for kings and queens, heroes and saints – in, as many believe, the presence of God – mere dreamers and story-tellers should be elevated to holiness in a place of their own.

Maybe you’ll find the experience as strange and wonderful as I did . . . because this was the morning after the announcement that Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse was to have a memorial stone placed in the Abbey. It transformed a jaunt across half the world for a bit of fun into a pilgrimage.

My little pilgrimage started as a follow-up to my trip last year to the biennial convention of The Wodehouse Society in Washington DC . After I shuffled off the plane home from the United States I vowed “never again”. These transcontinental flights were exhausting; my ageing overweight carcass couldn’t take the strain any more.

But when the P.G. Wodehouse Society (UK) – the UK is important, as I’ve explained before in these archives – advertised its biennial black-tie bash a few months later I placed myself at the head of the queue, all memories of torture by cattle class banished to the recesses of the mind where unpleasant experiences reside.

And so it was that I acquired a dinner suit , tried out the new Qantas Perth-London non-stop run and settled in at a boutique hotel in Bloomsbury just within (my) comfortable walking distance of the dinner venue at Gray’s Inn. I’d also booked a seat at the Blenheim Palace arts festival for the performance of a new Wodehouse show.

So that was it: two Wodehouse events in a fortnight of indulging myself with visiting friends and family, wining and dining, and touring as many of London’s railway termini as I could manage . I thought I might also try to see the Wodehouse archive at the British Library, and maybe head west to Bristol literally on the track of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Little did I know.

All I missed out on was the library, mainly because I’d failed to read properly the conditions of entry to the archive. I thought my passport would be enough ID to establish my bona fides but, no, the bureaucracy required proof of my residential (albeit foreign) address, a rate notice or something similar. As it happens, I don’t usually travel with that on my person. If I’d had my computer with me the ultra-polite custodian of the vaults would have accepted an electronic flash of a suitable document. Go figure, as the Americans say.

I did make a phone call after that, though, which would more than make up for the disappointment. Would it be possible, I inquired of Dulwich College, Wodehouse’s school, to come and visit its Wodehouse Library and memorial? I’ll get back to you, was the reply. I didn’t have much hope of a yes but it was worth the call.

I then trotted off expectantly to the Wodehouse dinner at Gray’s Inn [see Note 1 below], where 148 Wodehouseans gathered under the righteous gaze of a portrait gallery of eminent jurists for some celebratory browsing and sluicing, although we didn’t know until the very end just how celebratory the event would turn out to be.

Attendees to this 11th gala included some from the United States, the Netherlands, Germany and one from Australia – me, who was surprised and gratified to find the portrait of one R.G. Menzies [2] among those present, albeit in the reception room rather than the hall proper. The delicately nurtured came splendidly attired, of course, but among the male contingent black tie conformity was not, unfortunately, universal. One facially hirsute egg dared to appear in a white mess jacket with brass buttons . . . and he wore a soft-fronted shirt. Maybe he had the imprimatur of the Prince of Wales.

Gray’s Inn Hall . . . somewhere in the middle is the Duke of Kent

After the opening formalities, and with the banquet settling under the collective cummerbund, diners sat back to savour the traditional post-prandial concert of Wodehouse readings and songs. The program devised by the formidable Tony Ring was on the theme, A Comic Crook Parade – audacious, not to say impudent, given the judicial surroundings.

HRH the Duke of Kent, as he has often done before, led the gang in renderings from the works of the Great Man about the delights of the criminal life. They revived PGW’s very first professional lyric for the musical theatre, a lament of every old lag called Put Me in My Little Cell, from the 1904 West End show, Sergeant Brue:

Put me in my little cell

Let my job be soft,

Tell, oh tell the guv’nor that,

My heart with grief and pain is tore.

Say it’s all a blunder

That I’m not the chap they want . . .

They went on to perform Our Little Nest (from Oh, Lady, Lady!, 1918), We’re Crooks (Miss 1917, guess which year) and Tulip Time in Sing Sing (Sitting Pretty, 1914), before Lara Cazalet (Wodehouse’s step great-granddaughter) went straight with, of course, Bill (Oh, Lady, Lady! and Showboat, 1927).

The grand finale was the announcement of Plum’s elevation to Westminster Abbey, which opened up a whole new train of thought. As I hoofed it back to my hotel – getting a little lost among the unfamiliar surroundings of Bloomsbury – I became increasingly convinced of what I had to do next.

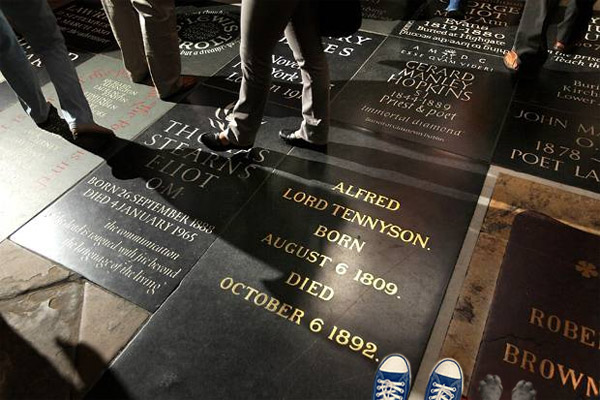

And the next morning I did it – I went directly to the Abbey and shuffled along in the tourist queue until I reached Poets’ Corner. The Abbey keepers have thoughtfully placed chairs around this space. I suppose they get used but I was the only one who took the opportunity that morning. The greatness on show there might not have been what the rest of the tourists had come to experience.

Behind me were the memorials to Chaucer and Shakespeare. Opposite was Oscar Wilde and right in front of me were stones holding the names of Ted Hughes and Philip Larkin. The floors and walls are covered with Milton, Pope, Dickens, Austen, the Bronte Sisters, both Eliots, Betjeman of course, Kipling, et al, and theatrical greats like Sheridan and Olivier (and, believe it or not, David Frost). I sat thinking for a good half-hour about how Plum might have regarded his being honoured with a place among such spirits, his elevation from one-time pariah [3] to immortal – and my own presence there. I’ve made my life out of the English language – it was like a homecoming.

Next day my Wodehouse pilgrimage continued to Blenheim Palace and its annual arts festival, for a one-off performance of the new show, Wodehouse in Wonderland. Blenheim is a magnificent pile near Oxford set in a vast park, an aristocratic edifice not unlike Blandings Castle, the ancient seat of the Earls of Emsworth [4], (Indeed my driver got lost later trying to find our way out. If it weren’t for some friendly natives, we’d still be there; the place is so big.) This is the ancestral home of the Dukes of Marlborough and the birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill. Daunting in every aspect.

William Humble in wonderland

Tucked away off a gallery on the lefthand side of the massive internal quadrangle is the Marlborough Room, a smallish space dominated by a huge portrait of the Duke. It was here that about 100 fans and festival-goers packed in to see the actor/singer Robert Daws go through his paces as Wodehouse himself in a biographical one-man show written by William Humble, a stranger to me. The piece as performed that day was still a work-in-progress, albeit fairly well along the path. Whether it will ever reach the spotlight as a fully formed commercial play remains to be determined.

Humble, who did his best to be so in a speech to the audience, has composed his play out of Plum’s own words – from his stories, his unreliable memoirs and his letters, and illustrated it with his lyrics to music by Jerome Kern, George Gershwin, Cole Porter and Ivor Novello — including my favourite, The Land Where the Good Songs Go (Kern). Of course I loved it. Daws, whom I had never seen or heard before the previous evening at Gray’s Inn, turned out to be one of those wonderful versatile performers who make up the huge English repertory company we see on TV all the time without knowing their names. He was, by turns, funny, dramatic and touching.

The bit I liked best – call me shallow if you like – was his rendition of the pig call from the story Pig-Hooey. Here’s how Wodehouse described it:

You want to begin the “hoo” in a low minor of two quarter notes in four-four time. From this build gradually to a higher note, until at last the voice is soaring in full crescendo, reaching F sharp on the natural scale and dwelling for two retarded half-notes, then breaking into a shower of accidental grace notes.

I’ve asked my friend the composer whether this is a valid musical sequence. He says it is but would not amount to much. Perhaps the vocalist is the key. According to Wodehouse:

You need a voice that has been trained on the open prairie and that has gathered richness and strength from competing with tornadoes. You need a manly, sunburned, wind-scorched voice with a suggestion in it of the crackling of corn husks and the whisper of evening breezes in the fodder.

I doubt whether Robert Daws, for all his virtues, has spent much time on the open prairie getting sunburned but, I tell you what, he called those pigs home like he was way out in the middle of Nebraska. Fair dinkum, I reckon there must have been porkers Down Under that day whose ears at least twitched at the sound.

With that ringing around my skull I set off westward to Bristol for a spot of admiring the works of the great Victorian engineer, railway, ship and bridge builder Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Three days later, nursing a bruised knee and the beginnings of a nasty infection in my leg (which kept me laid up, filled with antibiotics, for a fortnight after I got home), I was standing on Brunel’s Temple Meads station in Bristol, which serves his Great Western Railway, waiting for an uncertain train to London – an accident overnight in the rail corridor into London had disrupted all traffic from the west – when my phone rang. Can you come to Dulwich tomorrow – 11.30am or 3pm? And so it was that the next afternoon I rolled out of Victoria station for the short trip to Dulwich College, in a south-eastern suburb Wodehouse immortalised in a number of stories as Valley Fields.

Dulwich College (above) was founded in 1619 and, despite its longevity and record of achievement, it is still not regarded as being in the top rank of English public schools. The Empire might have been won on the playing fields of Eton but it was damned-well administered on the glowing greenswards surrounding Dulwich and other such “second-rankers”. Wodehouse was sent there in 1894, rising 13, and finished there in 1899. It was at Dulwich that he learnt the language skills that were the foundation of his literary art. Other famous Alleynians (named after the founder) include Ernest Shackleton, the Antarctic explorer and one of those heroic English failures, Raymond Chandler, the American crime novelist, Trevor “Barnacle” Bailey, the cricketer, and Nigel Farage, the Brexit politician.

I must say it felt faintly intimidating, even at my advanced age, for this son of a baby-boomer Queensland high school to go crunching along the gravel pathway to the Dulwich office under the clock tower and be introduced to Paul Fletcher, Head of Libraries and Archives for a one-on-one tour. I gathered that this was a privilege – not something they ordinarily did. The tour would be limited and quick.

Well, it was quick but essentially that was because the points of Wodehouse interest are grouped together – the Wodehouse Library, which houses the glassed-in memorial, and along the corridor, the Great Hall. The playing fields where Plum distinguished himself in cricket and rugby are all around. Paul actually took time to show me other souvenirs, such as Bailey’s England blazer, Shackleton’s Union Jack and the display featuring the Schools Class steam locomotive, Dulwich. He murmured interestedly when I told him one of my sons had actually played cricket at college on a tour with his Melbourne school in about 2000. He allowed me to take pictures.

The Great Hall (right) naturally reminded me of its equivalent at Market Snodsbury Grammar School, where Gussie presents the prizes in Right Ho, Jeeves: “[It had] been built somewhere in the year 1416, and, as with so many of these ancient foundations, there still seemed to brood over its Great Hall . . . not a little of the fug of the centuries . . . though somebody had opened a tentative window or two, the atmosphere remained distinctive and individual . . . The air was sort of heavy and languorous . . . with the scent of Young England and boiled beef and carrots.”

On the honour boards lining the hall’s dark timbers lurked the name of Pelham Grenville Wodehouse for some minor sporting achievement but I couldn’t spot it. More prominent was P.G.’s brother, Armine, posted for academic brilliance. The stained glass windows were not as magnificent as they had once been, Paul explained, as a result of the influence of a wayward bomb during the late unpleasantness.

So under the motto “There is no surer foundation for a beautiful friendship than a mutual taste in literature – P.G. Wodehouse”, we entered the library (with a picture of The Man on the wall behind reception) and its shrine (right) – a glassed-in corner of the establishment decked out like a study a writer might inhabit. It is lined with the complete works of P.G. Wodehouse. The desktop contains an old (and familiar to me) Remington Royal typewriter, pipes, photos, and a clutter of various other papers and knick-knacks.

On a side table are displayed a certificate of a prize awarded in 1894 to young Pelham for arithmetic and dictation, and next to it a copy of P.G. Wodehouse’s first published novel, The Pothunters, one of many school stories in which the budding novelist developed his skill and style. First editions in good condition are highly prized by collectors, and can change hands for more than $10,000. The Pothunters is dedicated to young family friends Joan, Effie and Ernestine Bowes-Lyon, first cousins to the Queen Mother. The inscription reads: “To William Townend [his lifelong schoolfriend] These first fruits of a genius at which the world will (shortly) be amazed (you see if it won’t) from the author P.G. Wodehouse Sep 28 1902”.

The bottom left corner of the desk is occupied by the visitors’ book, and on the open page now resides the signature of yours truly. Paul unlocked the door and let me into the inner sanctum just so I could pollute the paper. Not many had been there before me, although the line immediately above had been scratched only a week earlier by one Martin Breit, a German chap who, I later found out, had been at the Gray’s Inn dinner. I was so overwhelmed by this event that I snapped a quick picture of that side of the desk and left. Paul locked the door behind me and that was it.

Moments later I was thanking Paul profusely, heading somewhat dazedly out the door, back down the gravel path, through the security gate into the busy street, past the house where Plum had boarded when he first came to the school, off to my train and the rest of my life. I had been at Dulwich College half an hour. I came-to as the traffic roared past – I had not taken a selfie. Aaagh! If my leg hadn’t been so sore I would have performed an amazing gymnastic trick and kicked myself. How could I have had the run of the place and not put myself in the picture? At least I have proof of my visit with a snap of my signature in the guest book.

I loved my little pilgrimage. It became, I suppose like all pilgrimages, a journey of contemplation – why am I doing this; why have I been so moved by the work of a man who wrote for no greater reasons that he needed to make a living, he loved writing and he wanted to entertain his audience; what does the Abbey memorial mean in general, and to me in particular?

I have not reached any firm conclusions yet, and I don’t know that I ever shall.

NOTES

[1] Gray’s Inn is one of the four Inns of Court in London. To practise as a barrister in England and Wales a person must belong to one of these Inns, which are both professional associations and providers of chambers Gray’s Inn is ruled by a governing council made up of the Masters of the Bench (or Benchers). The Inn is known for its gardens, which have existed since at least 1597.

[2] Sir Robert Gordon Menzies (1894-1978), Australia’s longest serving Prime Minister, Honorary Bencher of Gray’s Inn and inter alia Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. The 1963 portrait hung at the Inn is one of several of him painted by the Australian artist Sir Ivor Hele.

[3] For non-Wodehouseans: Plum was interned in Nazi Germany in 1940, having failed to escape from France where he was living, and on release, under international law being aged nearly 60, notoriously made a series of radio broadcasts from Berlin. He was vilified in war-torn Britain and, although later cleared of everything but extraordinarily poor judgement, he lived the rest of his life in the United States and never even visited England again. The judicial reports on his conduct were kept secret for decades and it was not until weeks before his death in 1975 that he was knighted, apparently at the instigation and urging of the Queen Mother.

[4] Blandings Castle, which Wodehouse located in Shropshire, “came into existence towards the middle of the 15th century at a time when the landed gentry of England . . . believed in building their little nests solid. Huge, grey and majestic . . . The illustrated glossies often print articles about it, accompanied by photographs showing the park, the gardens, the yew alley and its other attractions”. The place boasts “ancient battlements, smooth green lawns, rolling parkland, majestic trees, well-bred-bees and gentlemanly birds”.